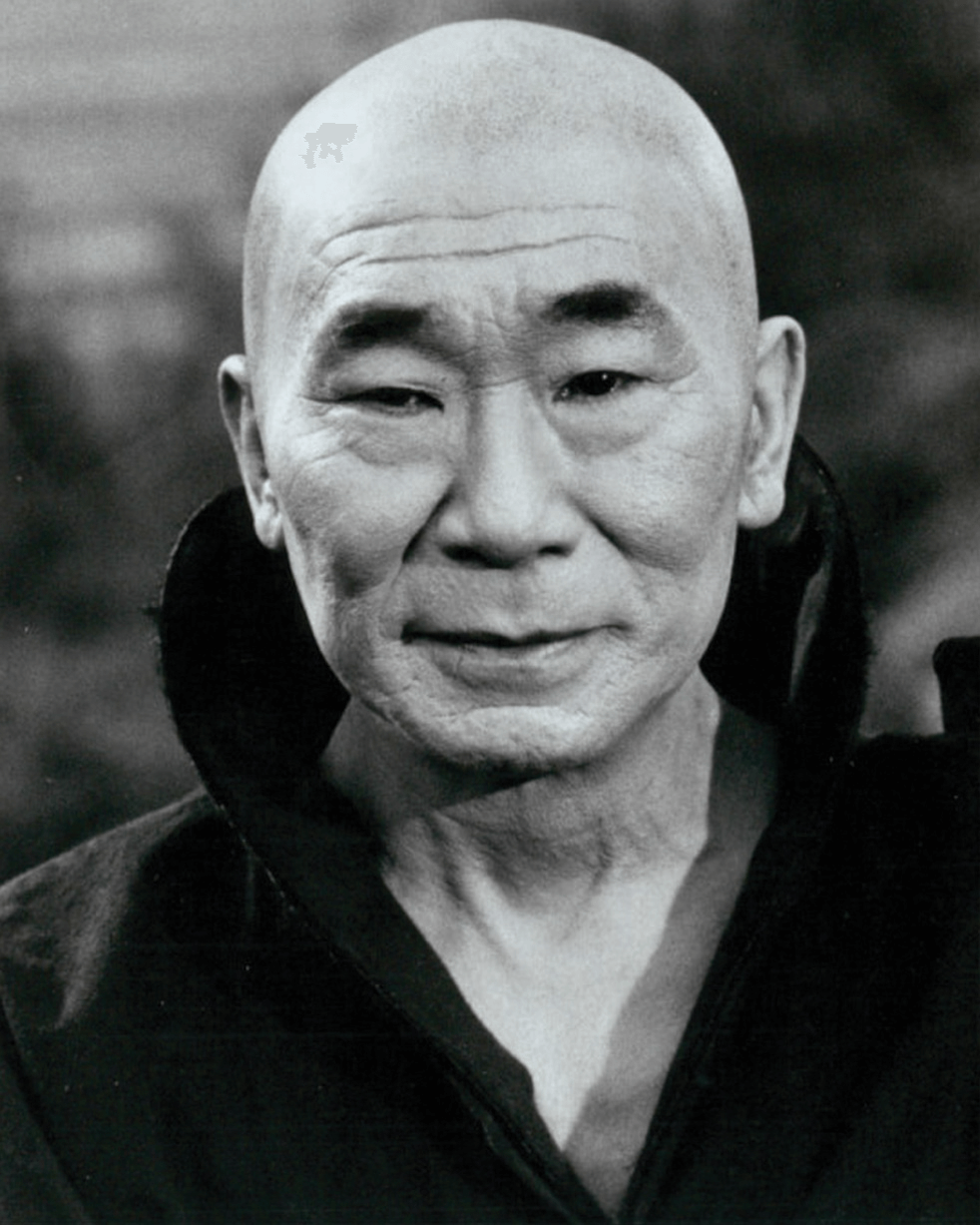

Pachappa Camp was founded in 1905 (possibly late 1904) by Dosan Ahn Chang Ho. The settlement was located in Riverside, CA and was home to around 300 Koreans at its height.

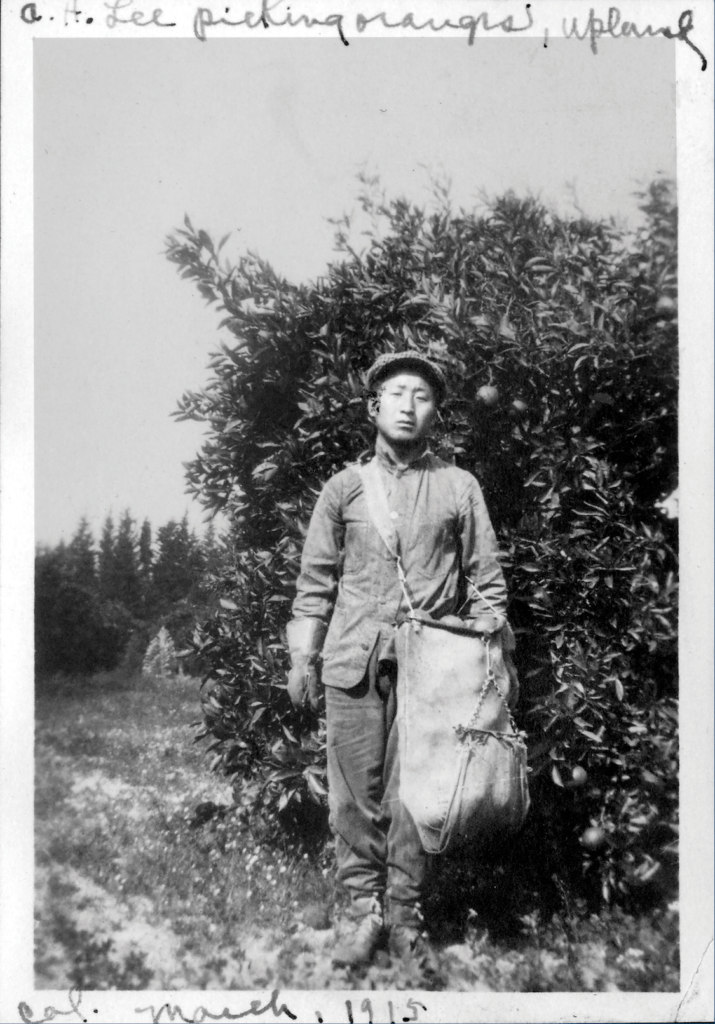

When Dosan arrived in Riverside on March 23, 1904, he immediately saw the need for a Korean Employment Agency. At the time, the Japanese American community had a monopoly on labor contracts. Thus, Dosan established a Korean Labor Bureau (KLB). Through the KLB, Koreans obtained jobs. Cornelius E. Rumsey, a local citrus farm owner and member of the Calvary Presbyterian Church in Riverside, was impressed with Dosan’s work ethic and decided to help the Korean American community.

Rumsey hired many of the Korean Americans living in Riverside. Dosan would later obtain a loan of $1,500 from Rumsey to establish the Korean Labor Bureau.

Pachappa Camp consisted of 20 buildings and a community hall. The buildings were drafty and one resident, Mary Paik Lee, wrote about her time at Pachappa recalling the living conditions in detail in her memoir Quiet Odyssey: A Pioneer Korean Woman in America.

Life at Pachappa was filled with activities including weddings, births, funerals, parties, and Korean independence movement meetings. The 1911 Korean National Association of North America meeting was held in December of that year.

Women and children lived at the camp, making it more than just a labor camp. Koreans were even buried at the local cemeteries. Soon Hak Kim, a member of the Korean National Association and a prominent member of Pachappa Camp, is buried at the local Evergreen Cemetery. In Soo Kim (who also went by Nin Soo Kim) had children. Some of his children stayed, lived, worked, and died in Riverside. Violet Catherine Kim, the last daughter of Yong Ryon Kim (he was the son of In (Nin) Soo Kim) lived in Riverside with her sisters Mallie and Lucy. Violet, who liked to go by Catherine, taught in Riverside and Grand Terrace. She befriended the Inaba family before the start of World War II. She and Meiko Inaba would later become friends after Meiko married into the Inaba family. Catherine and Meiko’s friendship would last a lifetime. Catherine died in 2018 and is buried near her parents at Olivewood Cemetery in Riverside, CA.

Pachappa Camp flourished for years and from 1905-1913, Koreans flocked to the citrus rich city of Riverside where jobs were plentiful. The settlement, which had been a Chinese railroad worker camp previously, housed men, women, and children. The local newspaper, the Riverside Press (now the Press Enterprise) reported on the camp several times, noting its size, community involvement, and activities. However, in 1913 the Great Citrus Freeze decimated crops in Riverside and jobs dwindled. Many of the citrus and fruit laborers in Riverside were forced to look elsewhere for work. Koreans ended up leaving Riverside in large numbers. Some went up north to Willows, Dinuba, and Reedley. Other Koreans went to Los Angeles and surrounding communities in Southern California. By 1918, Pachappa Camp would dwindle into a just a paltry number of families who ended up moving to Vine Street.

The story of Pachappa Camp was not known until UCR undergraduate students discovered a 1908 Sanborn Insurance map depicting the “Korean Settlement.” From there, Dr. Chang discovered Korean language newspaper articles in the Sinhan Minbo and other sources that confirmed his theory that Pachappa Camp was indeed the first Koreatown in America. The camp, which was also known as Dosan’s Republic, functioned as a community, developing cultural capital through its many activities.

The settlement and Dosan Ahn Chang Ho’s time in Riverside had not been discussed much, if at all, by scholars, according to Dr. Chang. But now, the settlement and its story has come to light.

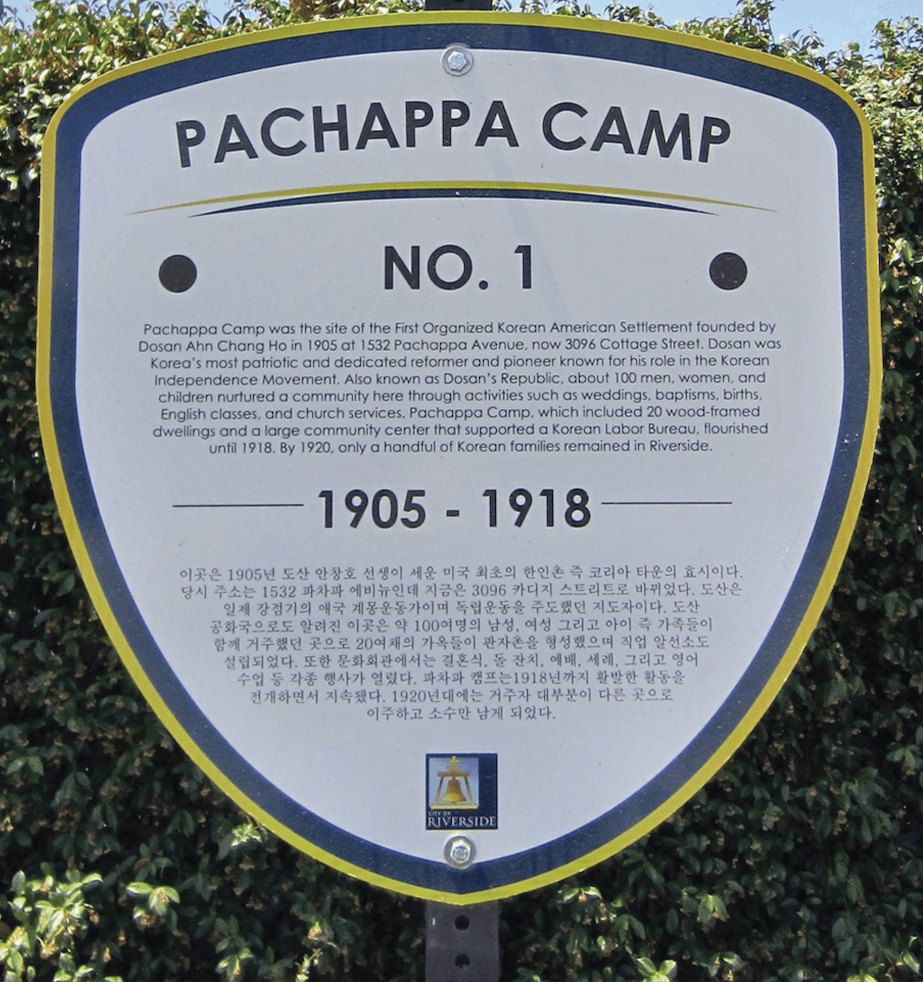

In December 2016, the city of Riverside voted to recognize Pachappa Camp as its first Point of Cultural Interest. On March 23, 2017, a dedication ceremony was held at the former site of Pachappa which is now at 3096 Cottage Street. A Southern California Gas Company fueling station now occupies much of the site. Today, a sign marks the location of what was once Pachappa Camp.